Rival explanations of the Poggendorff illusion

We should begin by locating my proposal in more detail in the context of other theories about these illusions.

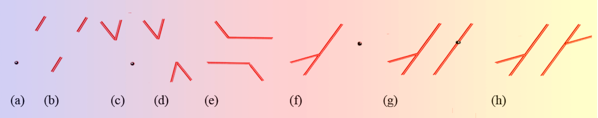

In different studies, the Poggendorff illusion - (h) in the sequence above - has been reduced, or amputated, as the term rather unattractively used in research papers puts it, to leave the variants shown above, all presenting to varying degrees illusory misalignment between test arms, or a test arm and a target dot.

However, for a start, not all specialists agree that all the misalignments under discussion belong to the same family of illusions (Morgan 1999). Even if the variants are all rightly thought of as related, there is no agreement that they are all primarily due to one common brain process, rather than a combination of different processes (Hotopf 1981).

Probably the leading culprit implicated in the misjudgments has been depth processing. The brain tries to make sense of the figure as a three dimensional array, it is argued, and error arises because of size-constancy effects, or ambiguities in the depth judgments involved (Gillam 1971; Gregory 1998). These are at first glance very plausible explanations. But looked at in detail, they seem to me to pose problems. Some demonstrations inconsistent with depth processing accounts appear on my separate visual illusions blog site.

Other researchers focus on two dimensional characteristics of the figures. In one account, illusion occurs because of our tendency to misjudge the size of angles (Ninio and O’Regan 1999). We certainly do misjudge angles, but it seems to me that we can convincingly demonstrate that Poggendorff effects cannot be attributed to these misjudgments. (Wenderoth 1981; Phillips 2006)

In other studies, misalignments arise because the figures trick the brain into getting the aim wrong in projecting alignment across the gap between the test lines, either because the position of the target points is misjudged, or because the orientation of the projected traverse is misjudged (for detailed summary review with references see Greene, 1994, page 666). That last option, a slight illusory rotation of the invisible agent in every variety of these figures, the traverse across the gap, is the one I favour.

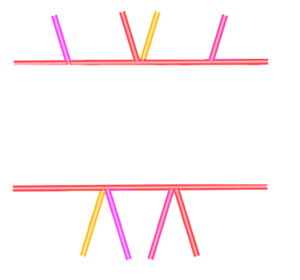

Rotation of the invisible traverse seems to me to account best for a paradoxical version of the Poggendorff figure, shown to the right. The apex of the upper central angle is the target point for two of the lower test arms, so that it seems paradoxically to be shifted at one and the same moment to the left for one test arm and to the right for the other. The same goes for the two lower target points. Appearances would be explained if the gap between the opposing parallels was illusorily reduced, but that can be shown not to be the culprit in Poggendorff illusions. No other systematic geometric distortion of the whole figure could account for all the simultaneous misalignments in the figure.

A Poggendorff paradox. The apex of the upper, downward pointing angle appears to move at one and the same time to the right in relation to the lower left angle, and to the left in relation to the lower right angle. Rotation of the invisible aiming tracks across the gap would account for the paradox.